Synchronization Tools

Background

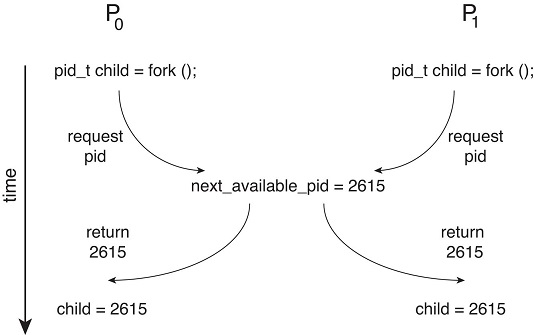

- Processes can execute concurrently.

- May be interrupted at any time, partially completing execution.

- Concurrent access to shared data may result in data inconsistency.

- Maintaining data consistency requires mechanisms to ensure the orderly execution of cooperating processes.

Bounded-Buffer – Shared-Memory Solution

- Shared data

#define BUFFER_SIZE 10

typedef struct {

. . .

} item;

item buffer[BUFFER_SIZE];

int in = 0;

int out = 0;- Solution is correct, but can only use BUFFER_SIZE-1 elements

Bounded-Buffer – Shared-Memory Solution

- Suppose that we wanted to provide a solution to the consumer-producer problem that fills all the buffers.

- We can do so by having an integer counter that keeps track of the number of full buffers.

- Initially, counter is set to 0. It is incremented by the producer after it produces a new buffer and is decremented by the consumer after it consumes a buffer.

Producer and Consumer

Producer

while (true) { /* produce an item in next produced */

while (counter == BUFFER_SIZE) ;

/* do nothing */

buffer[in] = next_produced;

in = (in + 1) % BUFFER_SIZE;

counter++;

}Consumer

Race Condition

- counter++ could be implemented as register1 = counter register1 = register1 + 1 counter = register1

- counter– could be implemented as register2 = counter register2 = register2 - 1 counter = register2

- Consider this execution interleaving with “ count = 5 ” initially:

- S0: producer execute register1 = counter {register1 = 5}

- S1: producer execute register1 = register1 + 1 {register1 = 6}

- S2: consumer execute register2 = counter {register2 = 5}

- S3: consumer execute register2 = register2 – 1 {register2 = 4}

- S4: producer execute counter = register1 {counter = 6 }

- S5: consumer execute counter = register2 {counter = 4}

Race Condition

- Critical Section Problem

- Consider system of n processes { \(p_0, p_1, … p_{n-1}\)}

- Each process has critical section segment of code

- Process may be changing common variables, updating table, writing file, etc

- When one process in critical section, no other may be in its critical section

- Critical section problem is to design protocol to solve this that the processes can use to synchronize their activity so as to cooperatively share data. Each process must request permission to enter its critical section.

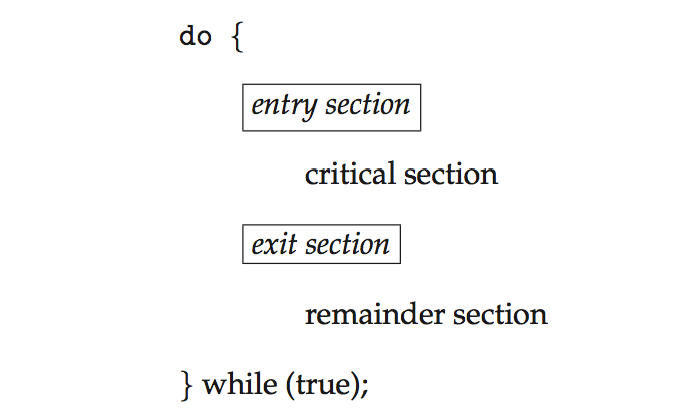

- Each process must ask permission to enter critical section in entry section , may follow critical section with exit section , then remainder section

- Each process has critical section segment of code

- Consider system of n processes { \(p_0, p_1, … p_{n-1}\)}

Critical Section

- General structure of process \(P_i\)

Solution to Critical-Section Problem

Mutual Exclusion - If process P i is executing in its critical section, then no other processes can be executing in their critical sections

Progress - If no process is executing in its critical section and there exist some processes that wish to enter their critical section, then the selection of the processes that will enter the critical section next cannot be postponed indefinitely

Bounded Waiting - A bound must exist on the number of times that other processes are allowed to enter their critical sections after a process has made a request to enter its critical section and before that request is granted

- Assume that each process executes at a nonzero speed

- No assumption concerning relative speed of the n processes

Solution to Critical-Section Problem

- The critical-section problem could be solved simply in a single-core environment if we could prevent interrupts from occurring while a shared variable was being modified.

- Unfortunately, this solution is not as feasible in a multiprocessor environment. Disabling interrupts on a multiprocessor can be time consuming, since the message is passed to all the processors. This message passing delays entry into each critical section, and system efficiency decreases.

Critical-Section Handling in OS

- Two approaches depend on if the kernel is preemptive or non-preemptive

- Preemptive – allows preemption of process when running in kernel mode.

- Pre-emptive kernels are especially difficult to design for SMP architectures

- But a preemptive kernel may be more responsive.

- A preemptive kernel is more suitable for real-time programming

- Non-preemptive – runs until exits kernel mode, blocks, or voluntarily yields CPU

- Essentially free of race conditions in kernel mode

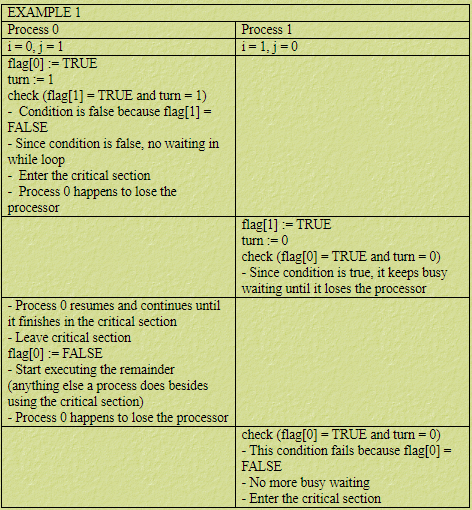

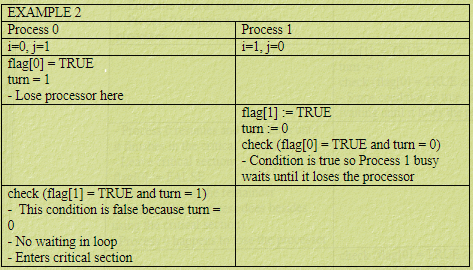

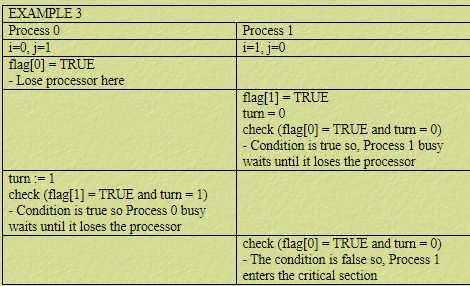

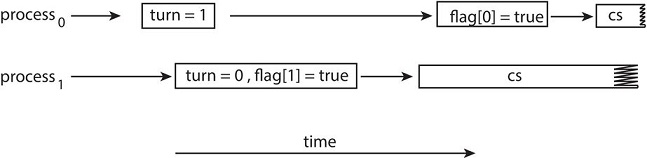

Peterson’s Solution

- Good algorithmic description of solving the problem

- Two process solution

Assume that the load and store machine-language instructions are atomic; that is, cannot be interrupted

The two processes share two variables:

- The variable turn indicates whose turn it is to enter the critical section

- The flag array is used to indicate if a process is ready to enter the critical section.

flag[i] = trueimplies that processP_iis ready! WhenP_iis preempted, we denoteP_jfor other process,j=1-i.

Algorithm for Process Pi

Algorithm for Process \(P_i\)

Algorithm for Process \(P_i\)

Algorithm for Process \(P_i\)

Peterson ’ s Solution (Cont.)

- Provable that the three CS requirement are met:

- Mutual exclusion is preserved \(P_i\) enters CS only if: either flag[j] = false or turn = i

- Progress requirement is satisfied

- Bounded-waiting requirement is met

Problem with Peterson’s Solution

Peterson’s solution is not guaranteed to work on modern computer architectures for the primary reason that, to improve system performance, processors and/or compilers may reorder read and write operations that have no dependencies.

As an example, consider the following data that are shared between two threads:

- where Thread 1 performs the statements

- and Thread 2 performs

- The expected behavior is, of course, that Thread 1 outputs the value 100 for variable x.

Problem with Peterson’s Solution

- However, as there are no data dependencies between the variables flag and x, it is possible that a processor may reorder the instructions for

- Thread 2 so that flag is assigned true before assignment of x = 100. In this situation, it is possible that Thread 1 would output 0 for variable x.

- Less obvious is that the processor may also reorder the statements issued by Thread 1 and load the variable x before loading the value of flag. If this were to occur, Thread 1 would output 0 for variable x even if the instructions issued by Thread 2 were not reordered.

- How does this affect Peterson’s solution? Consider what happens if the assignments of the first two statements that appear in the entry section of Peterson’s solution are reordered;

- it is possible that both threads may be active in their critical sections at the same time.

Synchronization Hardware

- Many systems provide hardware support for implementing the critical section code.

- All solutions below based on idea of locking

- Protecting critical regions via locks

- Uniprocessors – could disable interrupts

- Currently running code would execute without preemption

- Generally too inefficient on multiprocessor systems

- Operating systems using this not broadly scalable

- Modern machines provide special atomic hardware instructions

- Atomic = non-interruptible

- Either test memory word and set value Or swap contents of two memory words

Memory Barriers

- If a system may reorder instructions, a policy that can lead to unreliable data states.

- How a computer architecture determines what memory guarantees it will provide to an application program is known as its memory model. A memory model falls into one of two categories:

- Strongly ordered, where a memory modification on one processor is immediately visible to all other processors.

- Weakly ordered, where modifications to memory on one processor may not be immediately visible to other processors.

Memory Barriers

- When a memory barrier instruction is performed, the system ensures that all loads and stores are completed before any subsequent load or store operations are performed.

- Therefore, even if instructions were reordered, the memory barrier ensures that the store operations are completed in memory and visible to other processors before future load or store operations are performed .

- If we add a memory barrier operation to Thread 1

- we guarantee that the value of flag is loaded before the value of x.

Memory Barriers

- Similarly,

- We ensure that the assignment to x occurs before the assignment to flag.

- memory barriers are considered very low-level operations and are typically

- only used by kernel developers when writing specialized code that ensures mutual exclusion.

Hardware Instructions

- Many modern computer systems provide special hardware instructions that allow us either to test and modify the content of a word or to swap the contents of two words atomically —that is, as one uninterruptible unit.

- First one is test_and_set () instruction, the important characteristic of this instruction is that it is executed atomically.

- Thus, if two test_and_set () instructions are executed simultaneously (each on a different core), they will be executed sequentially in some arbitrary order.

- If the machine supports the test_and_set () instruction, then we can implement mutual exclusion by declaring a boolean variable lock, initialized to false.

- First one is test_and_set () instruction, the important characteristic of this instruction is that it is executed atomically.

Hardware Instructions

- Second one is compare_and_swap () instruction (CAS), just like the test_and_set () instruction, operates on two words atomically, but uses a different mechanism that is based on swapping the content of two words.

- The operand value is set to new_value only if the expression (*value == expected) is true. Regardless, CAS always returns the original value of the variable value.

- The important characteristic of this instruction is that it is executed atomically.

- Thus, if two CAS instructions are executed simultaneously (each on a different core), they will be executed sequentially in some arbitrary order.

Hardware Instructions

- Mutual exclusion using CAS can be provided as follows:

- A global variable (lock) is declared and is initialized to 0. The first process that invokes compare_and_swap () will set lock to 1.

- It will then enter its critical section, because the original value of lock was equal to the expected value of 0. Subsequent calls to compare_and_swap () will not succeed, because lock now is not equal to the expected value of 0.

- When a process exits its critical section, it sets lock back to 0, which allows another process to enter its critical section.

Bounded-waiting Mutual Exclusion with test_and_set

Hardware Instructions

- To prove that the progress requirement is met.

- Since a process exiting the critical section either sets lock to 0 or sets waiting[j] to false. Both allow a process that is waiting to enter its critical section to proceed.

- To prove that the bounded-waiting requirement is met:

- when a process leaves its critical section, it scans the array waiting in the cyclic ordering (i + 1, i + 2, …, n − 1, 0, …, i − 1).

- It designates the first process in this ordering that is in the entry section (waiting[j] == true) as the next one to enter the critical section.

- Any process waiting to enter its critical section will thus do so within n − 1 turns.

Atomic Variable

- Typically, the compare_and_swap () instruction is not used directly to provide mutual exclusion. Rather, it is used as a basic building block for constructing other tools that solve the critical-section problem.

- One such tool is an atomic variable, which provides atomic operations on basic data types such as integers and booleans .

- Incrementing or decrementing an integer value may produce a race condition. Atomic variables can be used in to ensure mutual exclusion in situations where there may be a data race on a single variable while it is being updated, as when a counter is incremented.

- As an example, the following increments the atomic integer sequence:

increment(&sequence); - where the increment() function is implemented using the CAS instruction:

Mutex Locks

- Previous solutions are complicated and generally inaccessible to application programmers

- OS designers build software tools to solve critical section problem, simplest is mutex lock

- Protect a critical section by first acquire() a lock then release() the lock

- Boolean variable indicating if lock is available or not

- Calls to acquire() and release() must be atomic

- Usually implemented via hardware atomic instructions

- But this solution requires busy waiting

- the lock therefore called a spinlock

Solution to Critical-section Problem Using Locks

- A mutex lock has a boolean variable available whose value indicates if the lock is available or not.

- If the lock is available, a call to acquire() succeeds, and the lock is then considered unavailable.

- A process that attempts to acquire an unavailable lock is blocked until the lock is released.

acquire() and release()

acquire() { while (!available)

; /* busy wait */

available = false;;

}

+ release() {

available = true;

}- Calls to either acquire() or release() must be performed atomically. Thus, mutex locks can be implemented using the CAS operation.

- The main disadvantage of the implementation given here is that it requires busy waiting.

- While a process is in its critical section, any other process that tries to enter its critical section must loop continuously in the call to acquire().

- This continual looping is clearly a problem in a real multiprogramming system, where a single CPU core is shared among many processes.

- The main disadvantage of the implementation given here is that it requires busy waiting.

Mutex Locks

- Busy waiting also wastes CPU cycles that some other process might be able to use productively.

- The type of mutex lock we have been describing is also called a spinlock because the process “spins” while waiting for the lock to become available. One alternative to avoid busy waiting by temporarily putting the waiting process to sleep and then awakening it once the lock becomes available. But that requires context switching.

- However, Spinlocks have an advantage in that no context switch is required when a process must wait on a lock, and a context switch may take considerable time.

- On modern multicore computing systems, spinlocks are widely used in many operating systems.

Semaphore

- Synchronization tool that provides more sophisticated ways (than Mutex locks) for process to synchronize their activities.

- Semaphore S – integer variable

- Can only be accessed via two indivisible (atomic) operations

wait() and signal(), originally called P() and V()

Definition of the wait() operation

Semaphore Usage

- Counting semaphore – integer value can range over an unrestricted domain.

- Counting semaphores can be used to control access to a given resource consisting of a finite number of instances.

- The semaphore is initialized to the number of resources available.

- Each process that wishes to use a resource performs a wait() operation on the semaphore (thereby decrementing the count).

- When a process releases a resource, it performs a signal() operation (incrementing the count).

- When the count for the semaphore goes to 0, all resources are being used. After that, processes that wish to use a resource will block until the count becomes greater than 0.

- Binary semaphore – integer value can range only between 0 and 1. It is same as a mutex lock

Semaphore Usage

- Can solve various synchronization problems

- Consider P1 and P2 that require S1 to happen before S2

- Create a semaphore “ synch ” initialized to 0

Semaphore Implementation

Mutex locks suffers from busy waiting and wait() and signal() semaphore operations has the same problem.

To overcome this problem, we can modify the definition of the wait() and signal() operations as follows:

- When a process executes the wait() operation and finds that the semaphore value is not positive, it must wait.

- However, rather than engaging in busy waiting, the process can suspend itself.

- The suspend operation places a process into a waiting queue associated with the semaphore, and the state of the process is switched to the waiting state.

- Then control is transferred to the CPU scheduler, which selects another process to execute.

- Then:

- A process that is suspended, waiting on a semaphore S, should be restarted when some other process executes a signal() operation.

- The process is restarted by a wakeup() operation, which changes the process from the waiting state to the ready state.

- The process is then placed in the ready queue.

Semaphore Implementation with no Busy waiting

- With each semaphore there is an associated waiting queue

- Each entry in a waiting queue has two data items:

- value (of type integer)

- pointer to next record in the list

- Two operations:

- block – place the process invoking the operation on the appropriate waiting queue

- wakeup – remove one of processes in the waiting queue and place it in the ready queue

Semaphore Implementation

- To implement semaphores under this definition:

- Each semaphore has an integer value and a list of processes list.

- When a process must wait on a semaphore, it is added to the list of processes.

- A signal() operation removes one process from the list of waiting processes and awakens that process.

Semaphore Implementation

- In this implementation:

- The semaphore values may be negative, whereas semaphore values are never negative under the classical definition of semaphores with busy waiting.

- If a semaphore value is negative, its magnitude is the number of processes waiting on that semaphore.

- The list of waiting processes can be easily implemented by a link field in each process control block (PCB).

- Each semaphore contains an integer value and a pointer to a list of PCBs.

Semaphore Implementation

- It is critical that semaphore operations be executed atomically.

- We must guarantee that no two processes can execute wait() and signal() operations on the same semaphore at the same time.

- This is a critical-section problem, and in a single-processor environment, we can solve it by simply inhibiting interrupts during the time the wait() and signal() operations are executing.

- In a multicore environment, interrupts must be disabled on every processing core, which is a difficult task and can seriously diminish performance.

- Therefore, SMP systems must provide alternative techniques—such as compare_and_swap () or spinlocks—to ensure that wait() and signal() are performed atomically.

Semaphore Implementation

- Thus, the implementation becomes the critical section problem where the wait and signal code are placed in the critical section

- Now may be we have busy waiting in critical section implementation

- Note that applications may spend lots of time in critical sections and therefore this is not a good solution

Liveness

- One consequence of using synchronization tools to coordinate access to critical sections is the possibility that a process attempting to enter its critical section will wait indefinitely.

- Liveness refers to a set of properties that a system must satisfy to ensure that processes make progress during their execution life cycle.

- A process waiting indefinitely under the circumstances just described is an example of a “liveness failure.”

- There are many different forms of liveness failure; however, all are generally characterized by poor performance and responsiveness.

- A very simple example of a liveness failure is an infinite loop. A busy wait loop presents the possibility of a liveness failure, especially if a process may loop an arbitrarily long period of time.

- Deadlocks

- Priority Inversion

Deadlock and Starvation

- Deadlock – two or more processes are waiting indefinitely for an event that can be caused by only one of the waiting processes

- Let S and Q be two semaphores initialized to 1

- Since these signal() operations cannot be executed, P0 and P1 are deadlocked.

- Starvation – indefinite blocking: A process may never be removed from the semaphore queue in which it is suspended

Liveness

- Priority Inversion – Scheduling problem when lower-priority process holds a lock needed by higher-priority process

- As an example, assume we have three processes—L, M, and H—whose priorities follow the order L < M < H.

- Assume that process H requires a semaphore S, which is currently being accessed by process L. Ordinarily, process H would wait for L to finish using resource S.

- However, now suppose that process M becomes runnable, thereby preempting process L. Indirectly, a process with a lower priority—process M—has affected how long process H must wait for L to relinquish resource S.

- This liveness problem is known as priority inversion , and it can occur only in systems with more than two priorities.

- Typically, priority inversion is avoided by implementing a priority-inheritance protocol . According to this protocol, all processes that are accessing resources needed by a higher-priority process inherit the higher priority until they are finished with the resources in question.

- When they are finished, their priorities revert to their original values

References

- A. Silberschatz, P.B. Galvin, and G. Gagne. Operating System Concepts , 10th Edition; 2018; John Wiley and Sons.

Related Topics

- Read Chapter 6 from book only: sections 6.1-6.6 & 6.8

Adapted from “Operating System Concepts”, 10th Edition; Abraham Silberschatz, Peter B. Galvin,Greg Gagne; 2018