1.6 Functions

Function is the fundamental feature of C programming language. Basically, a C program consists of a collection of functions related by calling dependences. The function call based programming paradigm is referred to as procedural programming.

Using functions has the following advantages.

- Reuse of code. It is better to use functions for those frequently used blocks of code. Write once and use many times.

- Support modular and structured design of programs. When dealing with a large and complex program, it is a practical strategy to decompose it into many modules for effective development and maintenance.

- Support divide-and-conquer algorithms to solve problems. Some problems can be solved by divide-and-conquer approach. For example, sorting by merge sort algorithm, which divides data into two parts, applies the merge sort to each parts, and then merges the sorted parts together. Such algorithm can be implemented effectively by recursive functions.

- Enable to divide a large source code program into many separate program files, which can be developed, compiled, and tested separately. This feature further enables creating function libraries and using existing libraries to create new libraries and application programs.

1.6.1 C functions

A function (also called procedure, subroutine, or method) is a block of code which can be called to run with or without passing parameters as inputs and get a result in return.

Example:

Listing 1: Example of global, static, and local variables.

#include<stdio.h>

int w; // global variable, visible from anywhere.

void f1(); // function name, function declaration/prototype, without return value

int f2(int); // function with return value and an int parameter

int f3();

int main() {

int x = 2; // declare local variable and initialize to 2

w = 1; // assign 1 to global variable w

f1(); // call f1

int y = f2(x); // declare int variable y, call f2 by passing value of x, assign the return value to y

printf("value: %d, %d\n", w, y);

printf("count: %d", f3()); // print the number of function calls

return 0;

}

void f1() { // function definition/implementation

f3();

int y = 2; // declare local variable and initialize to 2

w += y;

}

int f2(int x) { // x is an int parameter

f3();

int z = x + 2;

f1(); // call f1

return z; // return z, int type

}

int f3() {

static int counter = 0; // static variable, value will be retained between function calls

counter = counter + 1;

return counter;

}

/* output:

value: 5, 4

count: 4

*/1.6.2 Memory management of program executions

An executable program consists of a sequence of instructions organized by functions. Each function consists of a sequence of instructions. Each instruction consists a fixed number of bytes, i.e, 4 bytes in a 32-bit system, and 8 bytes in a 64-bit system. Let’s see how memory is used for running a program.

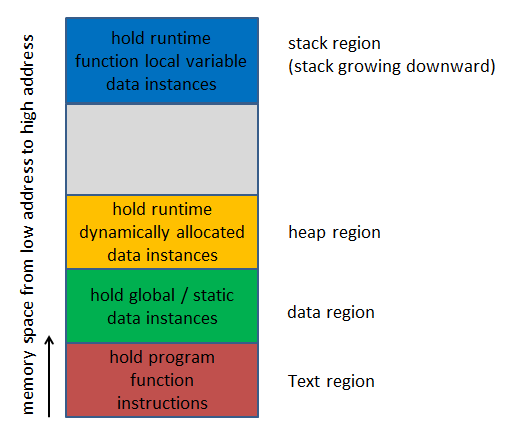

Conceptually, running an executable under an OS, the memory space to run the program is assigned by the OS. The memory space consists of two major parts: program memory and data memory. The program memory part has one region called text region (or text segment), used to store all function instructions. The data memory part has three regions (or segments):

- Data region, used to store static and global variables.

- Stack region, used to store the parameters and local variables of a function when the function is called.

- Heap region, used to store dynamically allocated memory blocks.

Figure 1 shows a conceptual diagram of the memory division for program execution.

When a program is called to run by an OS, it loads all functions to the text region, and static and global variables to the data region. The execution starts from calling the main function. When a function is called, the argument and local variables of the function are stored in the stack region by the program.

It is important to understand how program execution handles function argument and local variables during the execution of a function at runtime. The stack region is also called system stack or call stack. The term stack is used because it acts like a stack. When a function is called, the argument and local variables of the functions are pushed onto the call stack, namely memory spaces are reserved for these variables in the call stack. After that the argument and local variables are instantiated and have absolute addresses, which are used to access these variables such as copying parameter values to argument variables. After the function call is done, the argument and local variables of the function will be popped off from the call stack, so that the memory space in the call stack will be reused by other function calls.

Due to this memory management mechanism of function executions, the program will not remember the argument or local variables of a function call after the function call is completed. However, when a function, say f1, calls a function f2 inside f1, then argument and local variables of f2 will be pushed onto the call stack top of f1’s argument and local variables in the call stack. As a result, the call stack grows if there is a chained function calls like f1->f2->f3->f4. This may lead to stack overflow (supplementary link) if the call stack runs out space of the stack region.

Global and static variables

In case it needs to remember variable values used by different function calls, global variable or static variables can be used. Global variables and static variables are held in the data region, and will stay there during the execution of the program.

The global variables are shared by all functions, they can be used to pass values from one function to another function. However, global variables are less secure, hard to understand and debug, and less portable (not self-contained), so better not use them except that there is no alternative solution.

On the other hand, a local static variable in a function will have its data value retained after the function call, so it can be used to pass data from one call to another call of the same function. Listing 1 gives an example of static variable usage.

1.6.3 Function inputs and outputs

A function is usually designed to do a single algorithm on input data and to output the result. C provides two methods to pass input data into functions: pass-by-values and pass-by-references. C functions use return values or pass-by-references to output results.

1.6.4 Recursive functions

A function can call another function including itself. Calling a function itself inside the function is called recursive function call. Such functions are called recursive functions. More generally, if the dependent graph of a group of dependent functions form a cycle, e.g., f1->f2->f1, then they form a recursive function.

Example:

Problem: Create a function to compute the factorial n! = n*(n-1)*…2*1.

There are two types of algorithms to compute n!, recursive algorithm and iterative algorithm.

The recursive algorithm computes n! using recursive formula likes n! = n * (n-1)!, and is implemented by a recursive function as follows.

int factorial_recursive(int n) {

if (n <= 1)

return 1;

else

return n*factorial_recursive(n-1);

}The iterative algorithm uses a for loop to compute 1*2*3*…*n, and is implemented as follows.

int factorial_iterative(int n) {

int f = 1, i;

for (i=1; i<=n; i++)

f *= i;

return f;

}Both algorithms and implementations are correct, so what’s the differences between them? Now let’s do a simple analysis on time and memory usages of the two algorithms.

Calling factorial_recursive(n) results in a chained function calls: factorial_recursive(n)->factorial_recursive(n-1)->...->factorial_recursive(1), the call stack grows n times as much of a single function call. While calling factorial_iterative(n) just does one function call and the call stack won’t grow with n. Therefore, the factorial_recursive() function uses much more memory space than that of function factorial_iterative(). Therefore, running the factorial_recursive(n) function uses n times more memory space that running factorial_iterative(n) function.

For execution time, both algorithms do n times either function calls or loop blocks, so the execution time of both algorithms grows linearly with n. However, it takes more instructions to do a function call than that of the for loop. Therefore, factorial_iterative(n) runs faster than factorial_recursive().

In summary, we have the comparison of the two algorithms in terms of Big-O notation in the following table (We will look into the details of Big-O notations in Lesson 4).

| Algorithm | Time | Space |

|---|---|---|

| factorial_recursive | O(n) | O(n) |

| factorial_iterative | O(n) | O(1) |

We see that the iterative algorithm is more efficient than the recursive algorithm.

Even though the recursive algorithm is not efficient, it is effective (quick and easy) to implement for a problem solution derived by a recursion formula or by a Divide-and-Conquer method. We will look into recursive algorithms/functions in Lesson 6.

1.6.5 Preprocessors

Preprocessor directives are lines starting with #. They will be resolved in the preprocessing step. Using preprocessors is common in practical C programming. There are generally four types of usages.

1.6.6 C Libraries

A C library is a collection of predefined macro constants and functions, and can be reused in creating new programs. C standard comes with set standard library functions. Refer the list of GNU C89 and C99 supported library functions (supplementary link). C programmers can create extended C libraries using existing libraries, and further build a hierarchy of libraries.

Typically, a library usually has header files and object program files. A header file has file name extension .h, and contains function prototypes (declarations), type definitions, and macro definitions. The implementation of a library header has extension .c and contains the implementations of the functions declared in the header file. The implementation program files are compiled to object program file, which can be static with extension .lib to be used at linking stag to create the executable program, or dynamic with extension .dll to be used at execution time. The separation of function prototypes and implementation allows partial compilation without implementation, as well as different implementations for the same function prototypes. Particularly, function implementations are sometimes put in the header files for better portability.

The C89 library has 15 headers as shown in the following table. The standard library object programs comes with the compiler.

| Header | Description |

|---|---|

| assert.h | Diagnostics: assert macro, adding self-checks into a program |

| ctype.h | Character handling: functions for classifying characters and for case change |

| errno.h | Errors: functions for error message |

| float.h | Floating types: macros for float characteristic |

| limits.h | Integer type sizes: macros that describe the characteristics of integer and char types. |

| locale.h | Localization: functions to help a program adapt to a country or geographic region. |

| math.h | Mathematics: common mathematical functions including trigonometric, hyperbolic, exponential, logarithmic, power, nearest integer, absolute value, and remainder functions. |

| setjmp.h | Nonlocal Jumps: setjump and longjump functions to jump from one function to another functions |

| signal. h | Signal handling: functions that deal with exceptional signals. |

| stdarg.h | Variable arguments: tools for writing functions |

| stddef.h | Common definitions: definitions of frequently used types and macros. |

| stdio.h | Input/Output: standard device and file input/output functions. |

| stdlib.h | General utilities: functions that do not fit to other headers. |

| string.h | String handling: functions for string operations |

| time.h | Date and time: functions for determining the time and date. |

When a library function is used in programming, it needs to include the header file of the library so that the function can be called. When creating a standalone executable program, it needs .lib library files. For example, printf() is a function of stdio library, it needs to include stdio.h when using printf() in programs.

We will use C standard library functions, types and macros in stdio.h, stdlib.h, math.h, time.h, string.h, ctype.h in code examples and assignments. Now let’s look into two library functions printf() and scanf() declared in stdio.h.

Function printf() is a function for formatted screen output. printf() has calling syntax : printf(format control, list of variables);. It prints the list of variable values according to the format control.

The format control is of form: %<flag><field int><.precision int><size prefix><conversion char>. The following table gives some examples of the formats.

| Format examples | |

|---|---|

| %d or %i | print as decimal integer |

| %6d | print as decimal integer, at least 6 characters wide |

| %f | print as floating point number |

| %6f | print as floating point, at least 6 characters wide |

| %.2f | print as floating point, 2 characters after decimal point |

| %6.2f | print as floating point, at least 6 wide and 2 after decimal point |

| %x | print the hex value |

| %o | print the oct value |

| \n | print newline |

| \t | print tab |

Example:

int count = 10, sum = 100;

printf("count = %d sum = %d\n", count, sum);

printf("Pi = %10.2lf", 3.14159);

/* output:

count = 10 sum = 100

Pi = 3.14

*/scanf() is a functions for formatted keyboard input. It has calling syntax : scanf(format control, list of variable references);. It reads data from the keyboard, converts and stores the data in the referenced variables, and returns the number of successful readings.

Example:

int a;

float f;

scanf("%d %f", &a, &f); // pass by the reference of a and f. Function call scanf("%d %f", &a, &f); will wait user’s input from keyboard. After the user types a sequence of characters like 102 5.213 and hits the enter key, the program will read in string “102” and convert it to int value 102 and store in variable a, then read “5.213” and convert it to float 5.213 and store in f. The function will return 2 indicating 2 successful reads. If 102 abc is typed, then only 102 will be stored in a, and 1 will be returned.

The returned number can be used as an error checking for a valid input. If an invalid input is encountered, it can ask the user to input again until a valid input is given, see course code example prompt for user input.

1.6.7 Exercises

Self-quiz

Take a moment to review what you have read above. When you feel ready, take this self-quiz which does not count towards your grade but will help you to gauge your learning. Answer the questions posed below.